How can you estimate the value of research output? You could use pairwise comparisons, e.g., to ask specialists how much more valuable Darwin’s The Original of Species is than Dembski’s Intelligent Design. Then you can use these relative valuations to estimate absolute valuations.

Summary

Estimating values is hard. One way to elicit value estimates is ask researchers to compare two different items

Nuño Sempere had a post about eliciting comparisons of research value from

This post proposes some technical solutions to problems introduced to me in Nuño’s post. In particular, it includes principled ways to

estimate subjective values,

measure consistency in pairwise value judgments,

measure agreement between the raters,

aggregate subjective values.

I also propose to use weighted least squares when the raters supply distributions instead of numbers. It is not clear to me it is worth it to ask for distributions in these kinds of questions though, as your uncertainty level can be modelled implicitly by comparing different pairwise comparisons.

I use these methods on the data from the 6 researchers post.

I’m assuming you have read the 6 researchers post recently. I think this post will be hard to read if you haven’t.

Note: Also posted at the EA Forum. This document is a compiled Quarto file with source functions outside of the main document. The functions can be found in the source folder for this post. Also, thanks to Nuño Sempere for his comments on a draft of the post! Update 6/10/2022. Modified Gavin’s confidence interval for A Mathematical Theory to show the correct number. Update 4/11/2022. Some spelling fixes.

What’s this about

Table 1 contains the first

A list of questions in the data set.

knitr::kable(head(gavin[, 1:3]))| source | target | distance |

|---|---|---|

| Thinking Fast and Slow | The Global Priorities Institute’s Research Agenda | 100 |

| The Global Priorities Institute’s Research Agenda | The Mathematical Theory of Communication | 1000 |

| Superintelligence | The Mathematical Theory of Communication | 10 |

| Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law | The Vulnerable World Hypothesis | 10 |

| Shallow evaluations of longtermist organizations | The motivated reasoning critique of effective altruism | 10 |

| Shallow evaluations of longtermist organizations | Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law | 100 |

My first goal is to take relative value judgments such these and use them to estimate the true subjective values. In this case, I want to estimate the value that Gavin Leech places on every article in the data set, as contained in Table 2.

A list of questions in the data set.

levels <- levels(as.factor(c(gavin$source, gavin$target)))

knitr::kable(cbind(1:15, levels))| levels | |

|---|---|

| 1 | A comment on setting up a charity |

| 2 | A Model of Patient Spending and Movement Building |

| 3 | Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law |

| 4 | Center for Election Science EA Wiki stub |

| 5 | Database of orgs relevant to longtermist/x-risk work |

| 6 | Extinguishing or preventing coal seam fires is a potential cause area |

| 7 | Reversals in Psychology |

| 8 | Shallow evaluations of longtermist organizations |

| 9 | Superintelligence |

| 10 | The Global Priorities Institute’s Research Agenda |

| 11 | The Mathematical Theory of Communication |

| 12 | The motivated reasoning critique of effective altruism |

| 13 | The Vulnerable World Hypothesis |

| 14 | Thinking Fast and Slow |

| 15 | What are some low-information priors that you find practically useful for thinking about the world? |

The article Categorizing Variants of Goodhart’s Law has value fixed to

A model with multiplicative error terms

Motivation and setup

Let

which is a linear regression model. It looks like a two-way analysis of variance, but isn’t quite that, as we are only dealing with one factor here (the evaluated research) which appears twice in each equation. That said, the only difficulty in estimating this model is to make a model matrix for the regression coefficients. Observe that the residual standard deviation is fixed across items. We’ll take a look at how to reasonably relax this later on.

Incidence matrices

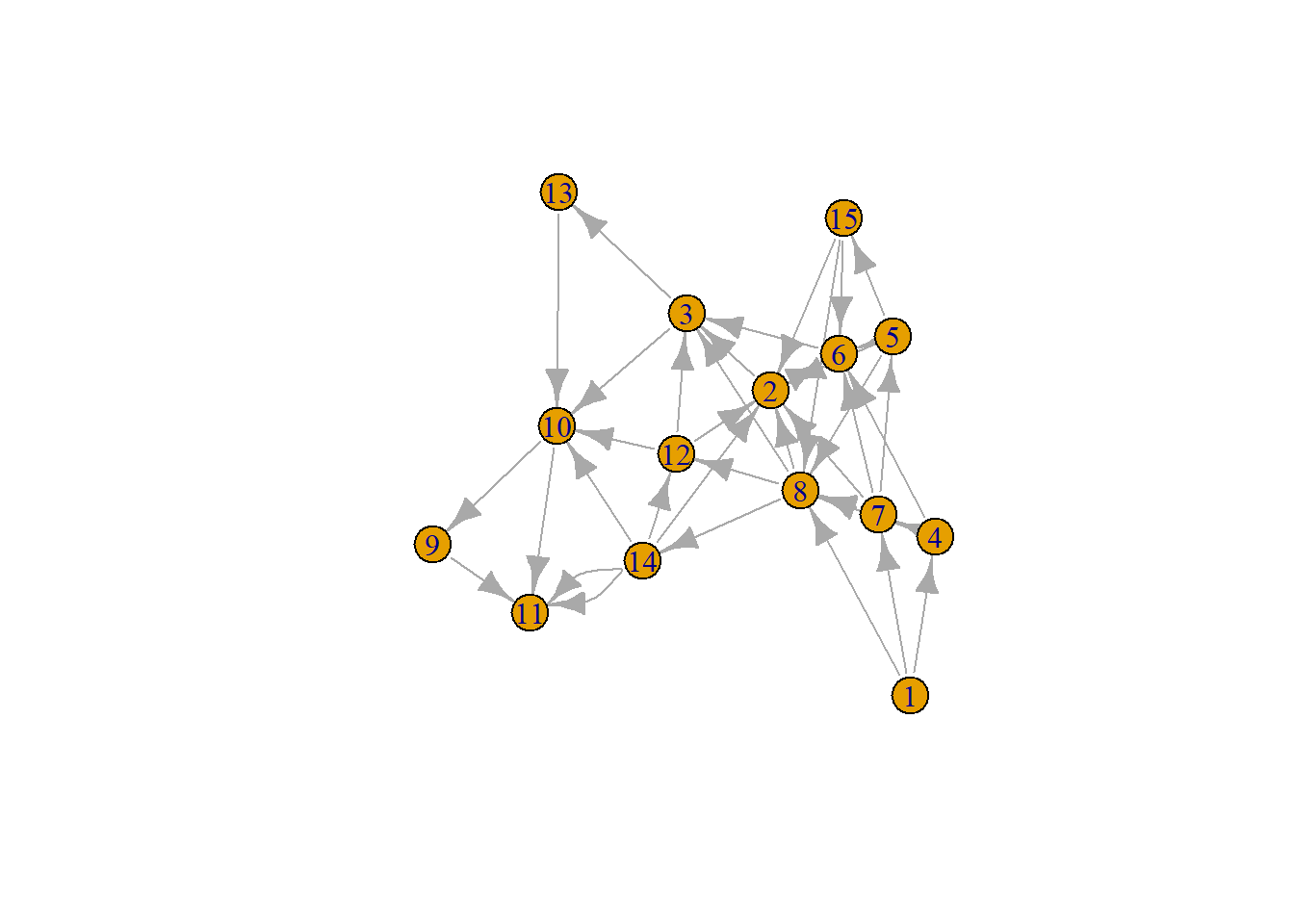

The questions Gavin answered in the table above can be understood as a directed graph; I’ll call it the question graph. Figure 1 below contains Gavin’s question graph.

Plotting question graph for Gavin.

levels <- levels(as.factor(c(gavin$source, gavin$target)))

source <- as.numeric(factor(gavin$source, levels = levels))

target <- as.numeric(factor(gavin$target, levels = levels))

graph <- igraph::graph_from_edgelist(cbind(source, target))

plot(graph)Directed graphs can be defined by their incidence matrices. If

Table 3 contains Gavin’s incidence matrix.

Calculation of incidence matrix for Gavin.

n <- nrow(gavin)

k <- 15

b <- matrix(data = 0, nrow = n, ncol = k)

for (i in seq(n)) {

b[i, source[i]] <- -1

b[i, target[i]] <- 1

}

knitr::kable(t(b))| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Now we can verify that

Example

We fit a linear regression to Gavin’s data. Table 4 contains the resulting estimates on the log-scale, rounded to the nearest whole number.

Parameter estimates for Gavin.

mod <- pairwise_model(gavin, fixed = 3, keep_names = FALSE)

vals <- round(c(coef(mod)[1:2], q3 = 0, coef(mod)[3:14]))

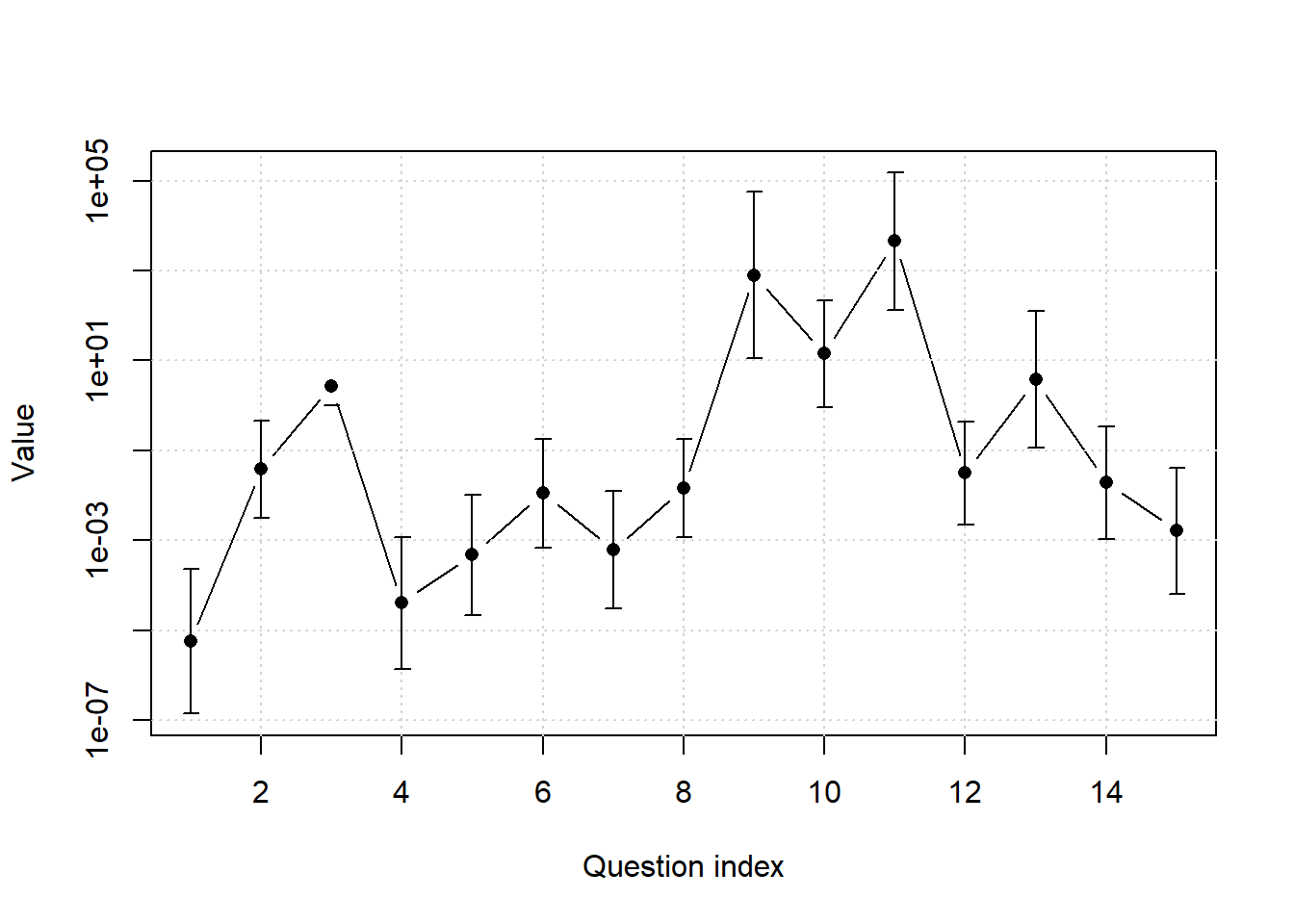

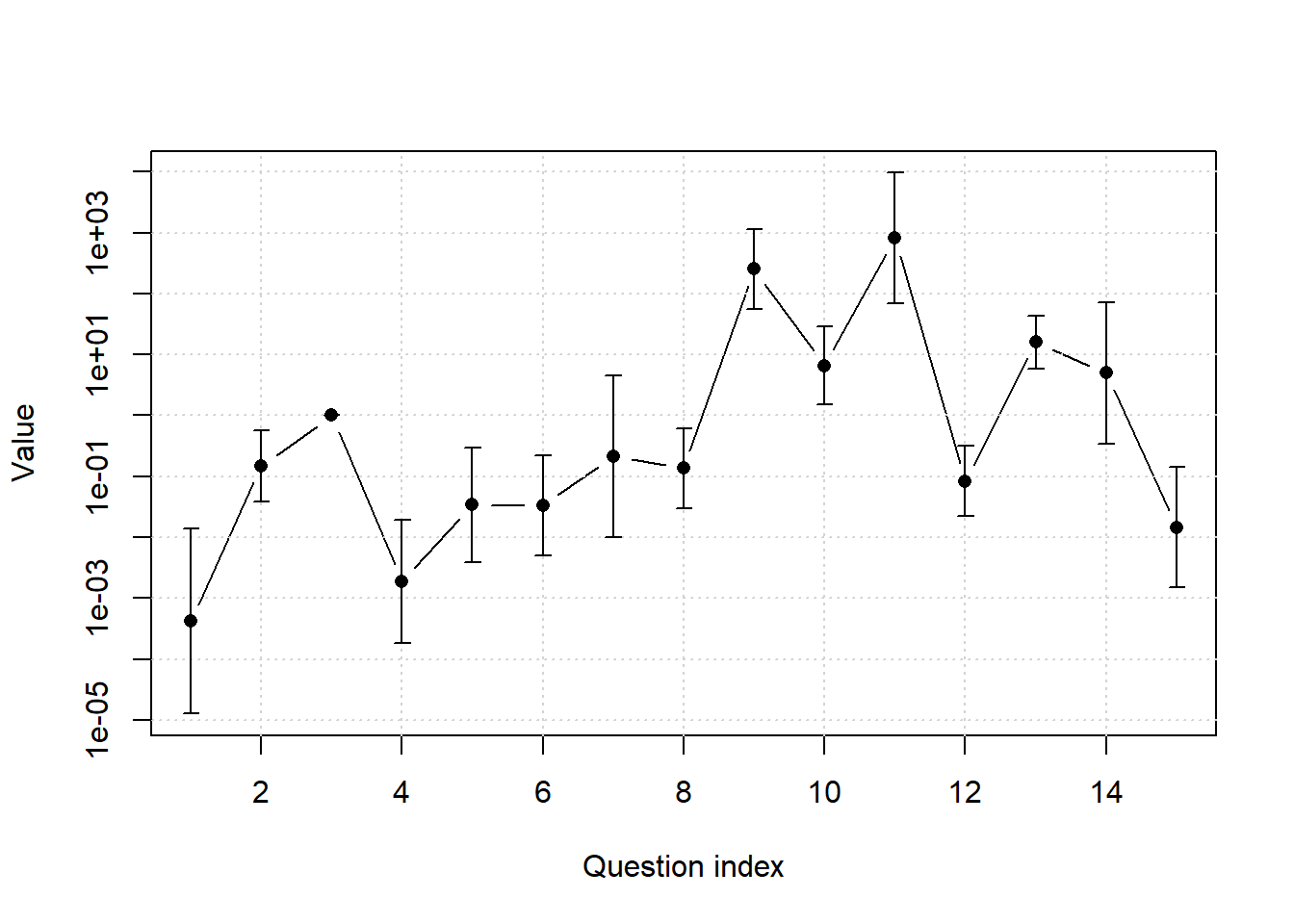

knitr::kable(t(vals))We can also make confidence intervals for the questions using the confint function. Figure 2 plots confidence intervals for all the

Plot of parametes and error bars.

exped = exp(confint(mod))

confints = rbind(exped[1:2, ], c(1, 1), exped[3:14, ])

rownames(confints) <- 1:15

params <- setNames(c(coef(mod)[1:2], 1, coef(mod)[3:14]), 1:15)

Hmisc::errbar(x = 1:15, y = exp(params), yplus = confints[, 2], yminus = confints[, 1],

log = "y", ylab = "Value", xlab = "Question index", type = "b")

grid()

Hmisc::errbar(x = 1:15, y = exp(params), yplus = confints[, 2], yminus = confints[, 1],

add = TRUE)The

confints[11, ] 2.5 % 97.5 %

135.4981 150222.4654 That’s really wide!

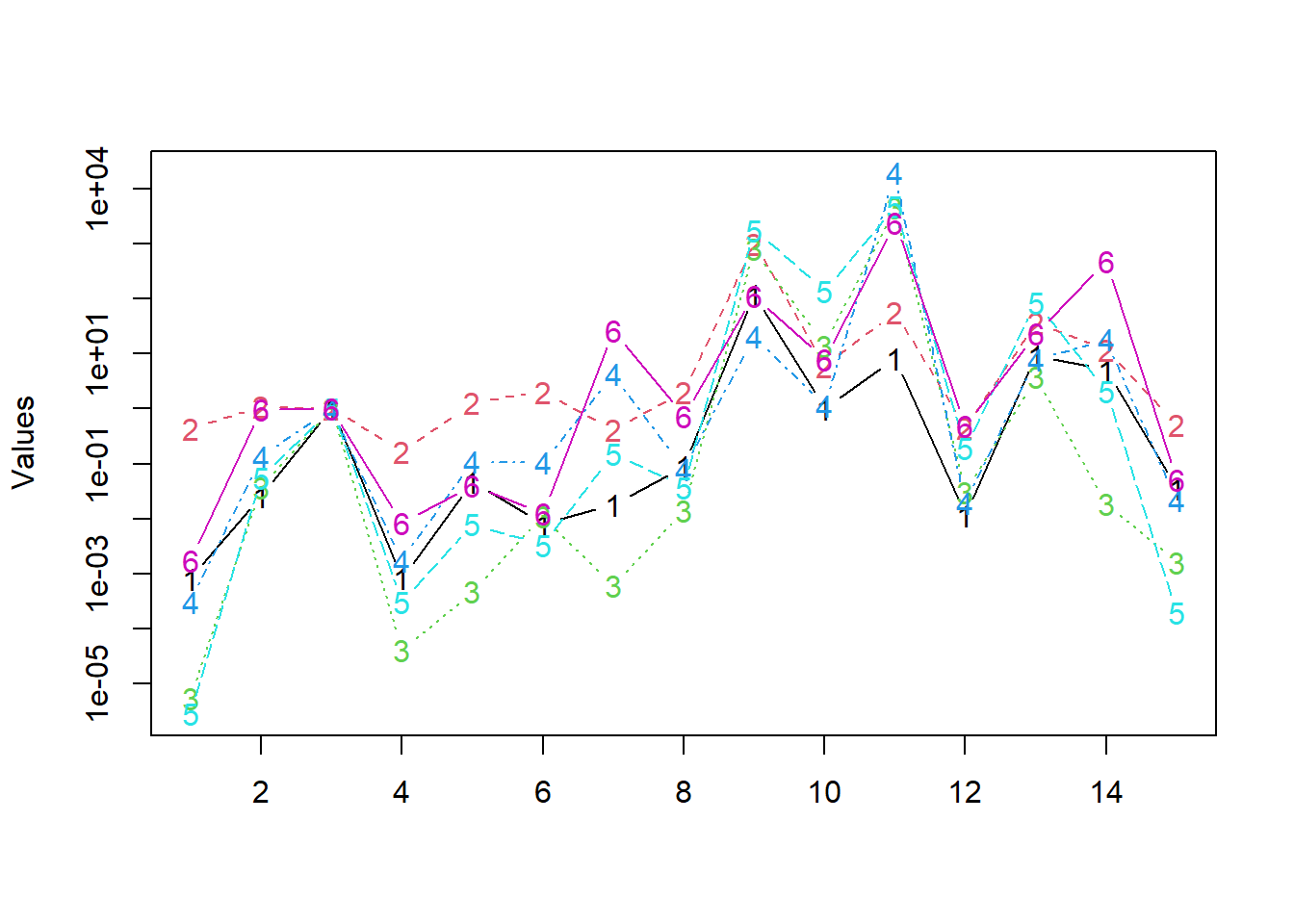

All the raters

The raters have IDs given in this table.

x <- setNames(1:6, names(data_list))

knitr::kable(t(x))| linch | finn | gavin | jamie | misha | ozzie |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

We fit the model for all the raters and plot the resulting estimates in Figure 3. Notice the log-scale.

Function for plotting results for all raters.

parameters = sapply(

data_list,

\(data) {

coefs <- exp(coef(pairwise_model(data)))

c(coefs[1:2], 1, coefs[3:14])

})

matplot(parameters, log = "y", type = "b", ylab = "Values")It seems that the raters agree quite a bit.

Measuring agreement

One of the easiest and most popular ways to measure agreement among two raters is Lin’s concordance coefficient (aka quadratically weighted Cohen’s kappa). It has an unpublished multirater generalization

Calculate concordance of the parameters.

concordance = function(x) {

n = nrow(x)

r = ncol(x)

sigma = cov(x) * (n - 1) / n

mu = colMeans(x)

trace = sum(diag(sigma))

top = sum(sigma) - trace

bottom = (r - 1) * trace + r ^ 2 * (mean(mu^2) - mean(mu)^2)

top / bottom

}

concordance(log(parameters))[1] 0.698547I’m impressed by the level of agreement among the raters.

We can also construct a matrix of pairwise agreements.

Defines the concordanc matrix using Lin’s coefficient.

concordances <- outer(seq(6), seq(6), Vectorize(\(i,j) concordance(

cbind(log(parameters)[, i], log(parameters)[, j]))))

colnames(concordances) <- names(x)

rownames(concordances) <- names(x)

concordances linch finn gavin jamie misha ozzie

linch 1.0000000 0.5442018 0.7562977 0.7705449 0.7779404 0.7016672

finn 0.5442018 1.0000000 0.4031429 0.5385316 0.4685602 0.5985986

gavin 0.7562977 0.4031429 1.0000000 0.7237382 0.9106108 0.5996458

jamie 0.7705449 0.5385316 0.7237382 1.0000000 0.8253265 0.8926464

misha 0.7779404 0.4685602 0.9106108 0.8253265 1.0000000 0.7804517

ozzie 0.7016672 0.5985986 0.5996458 0.8926464 0.7804517 1.0000000Now we notice, e.g., that (i) Gavin agrees with Misha, (ii) Finn doesn’t agree much with anyone, (iii) Ozzie agrees with Jamie.

Identification of the parameters

The parameters

Now, it should be intuitively clear that

Measuring inconsistency

Recall the multiplicative equation for the reported distance:

The consistencies of our 6 player are

Defines the consistencies of all raters.

consistencies = lapply(data_list, \(data) summary(pairwise_model(data))$sigma)

knitr::kable(tibble::as_tibble(consistencies), digits = 2)| linch | finn | gavin | jamie | misha | ozzie |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.87 | 1.04 | 2.22 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

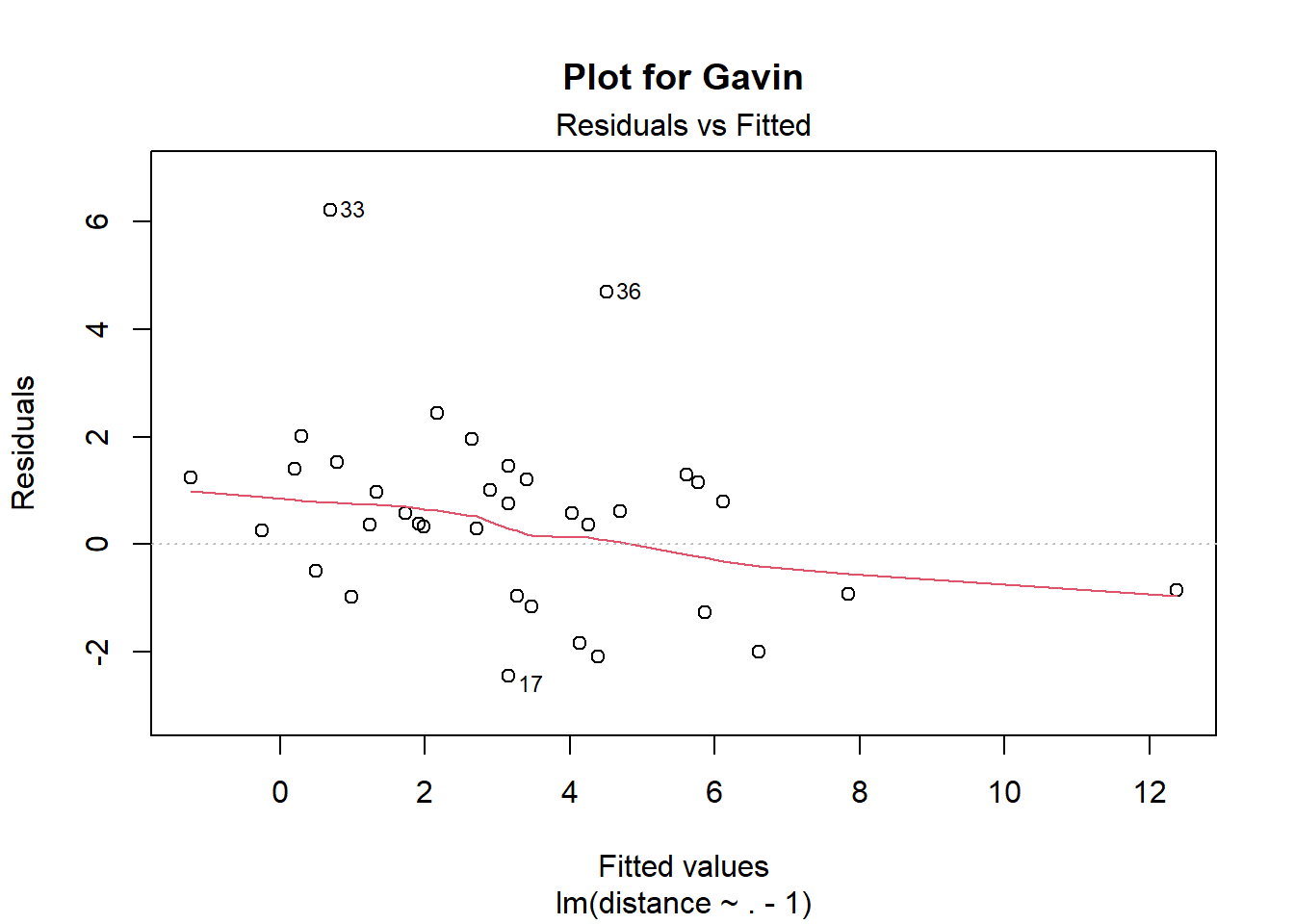

All of these are roughly the same, except Gavin’s. That might be surprising since Nuño claimed Gavin is the most consistent of the raters. His inconsistency score is probably unfavourable since he has some serious outliers in his ratings, not because he’s inconsistent across the board. Ratings

plot(mod, which = 1, main = "Plot for Gavin")

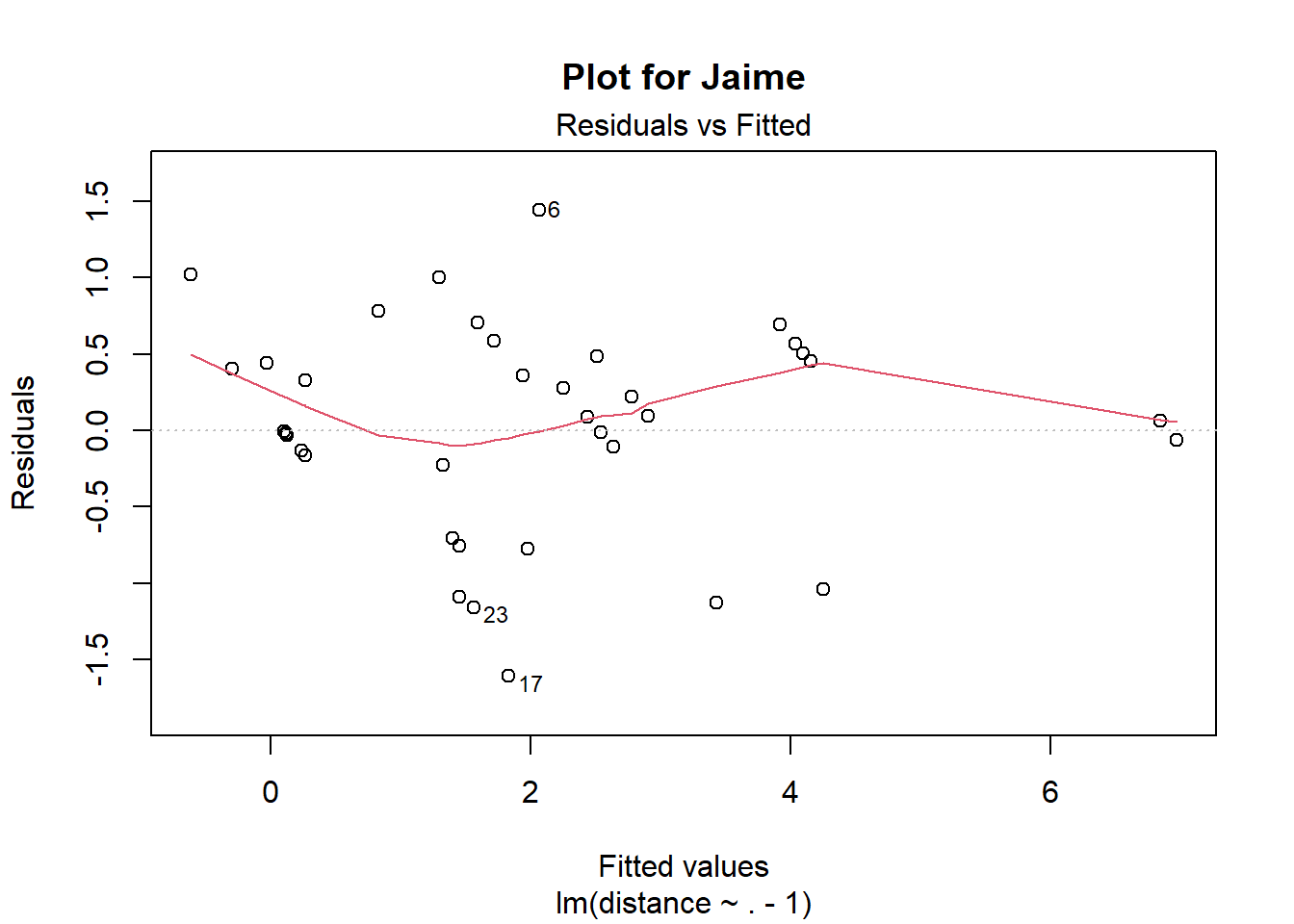

Compared it to the same plot for Jaime Sevilla.

plot(pairwise_model(jamie), which = 1, main = "Plot for Jaime")

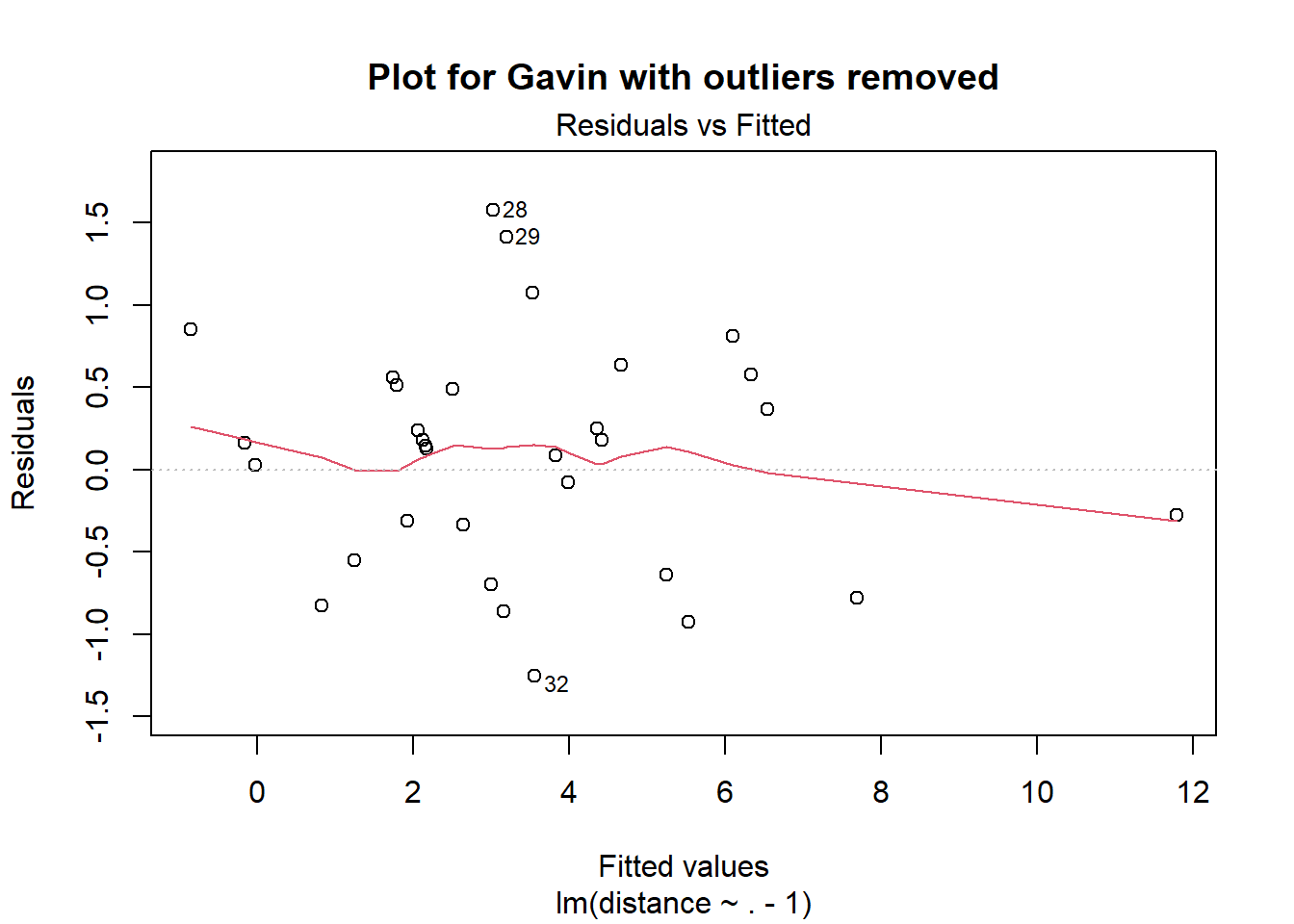

Let’s see what happens if we remove the observations

gavin_ <- gavin[setdiff(seq(nrow(gavin)), c(31, 33, 34, 36)), ]

plot(pairwise_model(gavin_), which = 1, main = "Plot for Gavin with outliers removed")

The residual plot looks better now, and the inconsistency score becomes

My take-away is that it would be beneficial to use robust linear regressions when estimating rlm.

You shouldn’t strive for consistency

Striving for consistency requires you to follow a method. For instance, you can write down or try hard to remember what you have answered on previous questions, then use the right formula to deduce a consistent answer. I would advice against doing this though. When you compare two items against each other, just follow the priming of the shown items and let the statistical method do its work! If you’re trying hard to be consistent you’ll probably introduce some sort of bias, as you’ll essentially make the ratings dependent on their ordering. Also see the crowd within. The value-elicitation framework is similar to psychometrics, where you want every measurement to be as independent of every other measurement as possible when you condition on the latent variables.

I also see little reason to use algorithms that prohibits cyclical comparisons, as there is no statistical reason to avoid them. (Only a psychological one, if you feel like you have to be consistent.) It’s also fine the ask the same question more than once – at least if you add some addition correlation term into the model. And have some time distance between the questions.

Aggregation

We estimate

Conceptually, this model implies that there is a true underlying

Using lme4, I made a function pairwise_mixed_model that fits a mixed effects model to the data without an intercept. Check out the source if you want to know exactly what I’ve done.

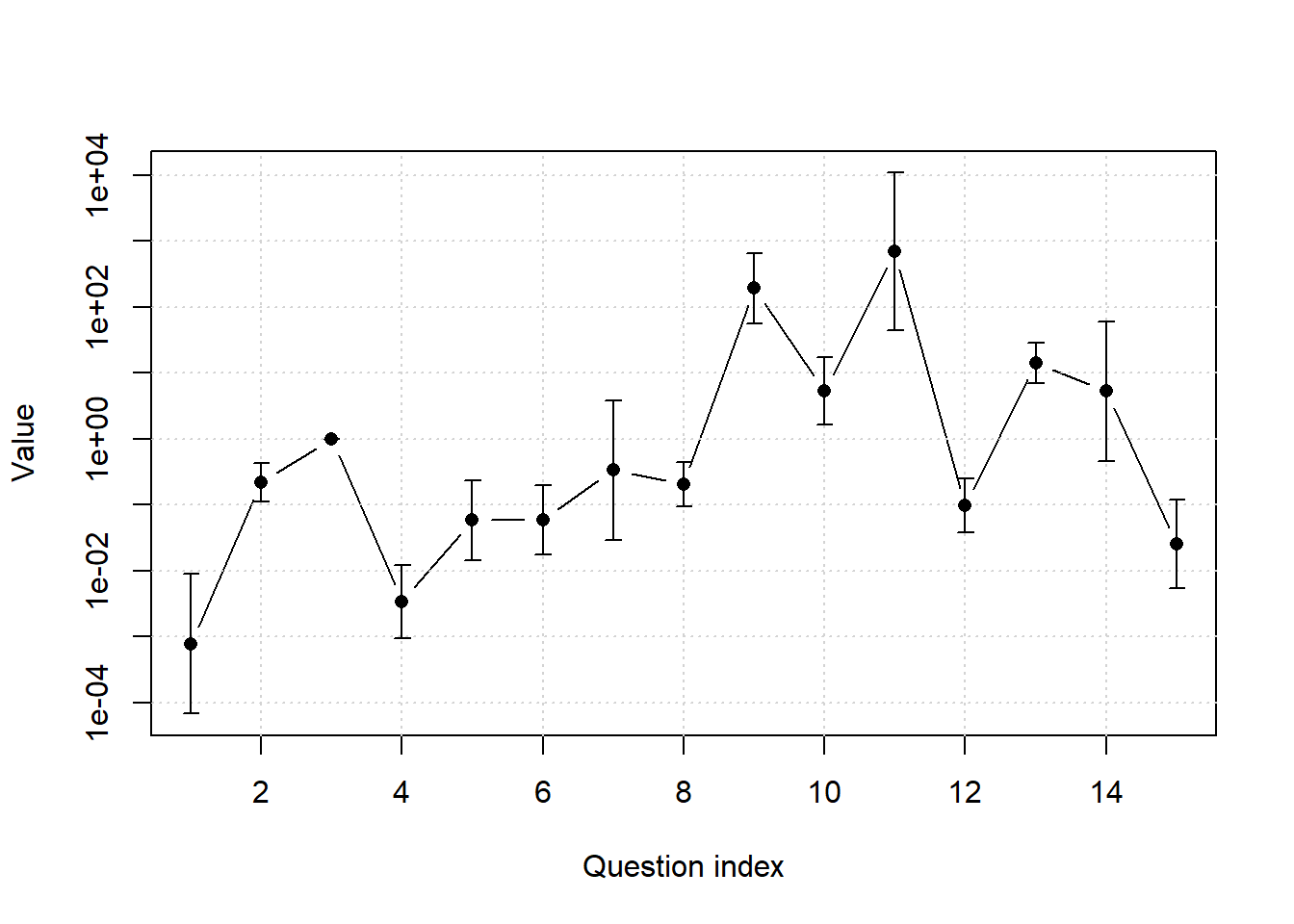

mod <- pairwise_mixed_model(data_list, fixed = 3)boundary (singular) fit: see help('isSingular')Using the mod object, we can plot (Figure 4) confidence intervals and estimates for the aggregate ratings.

Defines confidence intervals and estimates used for plotting.

conf <- confint(mod, method = "Wald")[16:29, ]

params <- c(lme4::fixef(mod)[1:2], 0, lme4::fixef(mod)[3:14])

exped <- rbind(exp(conf)[1:2, ], c(1,1), exp(conf)[3:14, ])

Hmisc::errbar(x = 1:15, y = exp(params), yplus = exped[, 2], yminus = exped[, 1],

log = "y", ylab = "Value", xlab = "Question index", type = "b")

grid()

Hmisc::errbar(x = 1:15, y = exp(params), yplus = exped[, 2], yminus = exped[, 1],

add = TRUE)The confidence intervals in the plot are reasonably sized, but remember the

Confidence interval for Mathematical Theory of Communication with uncorrelated random effects.

round(exp(confint(mod, method = "Wald")[16:29, ])[10, ]) 2.5 % 97.5 %

44 10740 The uncertainty of the aggregate value is smaller than that of Gavin’s subjective value. But the uncertainty is still very, very large. I think the level of uncertainty is wrong though. Fixing it would probably require a modification of the model to allow for items of different difficulty, or maybe a non-multiplicative error structure. But there is also a counterfactual aspect here. It’s hard to say how quickly someone else would’ve invented information theory weren’t it for A Mathematical Theory. Different “concepts” about counterfactuals could potentially lead to different true

Incorporating uncertainty

Instead of rating the ratio

The formal reasoning behind this proposal goes as follows. If

In the summary I wrote that it’s not clear to me that it’s worth it to ask for distributions in pairwise comparisons, as your uncertainty level can be modeled implicitly by comparing different pairwise comparisons. What does this mean? Let’s simplify the model in Equation 1 so it contains two error terms,

This models allows you to have different uncertainties for different items, but doesn’t allow for idiosyncratic errors depending on interactions between the